Slack time explained

What problem are we trying to solve?

You're a software product team. Your job is to steadily deliver working product. Generally this means there's two types of work you're going to do:

- Work that directly correlates to delivering value to the customer

- Work that directly correlates to the ability to keep on delivering value at the same pace

In "agile" terminology, those categories are labeled, respectively, "stories" and "tech debt".

There is tension between these two. We want to deliver as much value as possible ALL THE TIME. In a perfect world, with perfect knowledge and perfect skill, we would never need to do any of the second category of work. However, as James Shore1 once said, "as soon as our fingers touch the keyboard, we add tech debt."

As soon as our fingers touch the keyboard, we add tech debt.

— James Shore

This means that, unerringly, unfailingly, the team will need to do some of the second category of work.

Given this, the problem statement is as follows:

What is the simplest way to manage both types of work that the team needs to do which allows the team to maintain a focus on the delivery of work that is valuable to the customer?

Let's define a tool that we'll call "velocity"

We'll define "velocity" as "the amount of work, deliverable by the team in a given unit of time, which directly correlates to value to the customer." In other words, velocity = work / time 2.

This provides a baseline, a point of calibration, for the team's ability to deliver work that correlates to value. We can now say "The team is able to deliver X work in Y time."

The easy next question is, how do we define the time? Well, often we just use one- or two-week timespans. We don't have to search too hard for this.

The harder next question is, how do we define "amount of work?". I've written a blog entry on the answer to that question, so I'll say it in one sentence here: we choose an internally self-consistent method of evaluating the complexity of given units of work, relative to other units of work, and we call this "estimates."

What this allows us to do is add these estimates together and obtain something self-consistent that can be used to understand how the team's delivery of work is evolving.

Our new formula is: velocity = estimates / time .

Let's explore some of the consequences of doing this

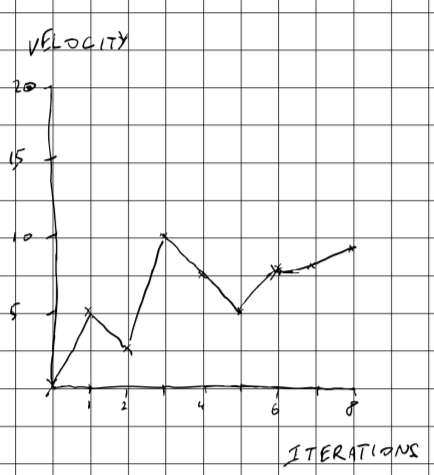

Using the estimates to measure velocity, as explained above, can yield the following graph when we look at how much work a squad can deliver.

#+caption:Velocity per iteration

To note, this does not say anything about how much people work, it just says how much estimated complexity of work was delivered.

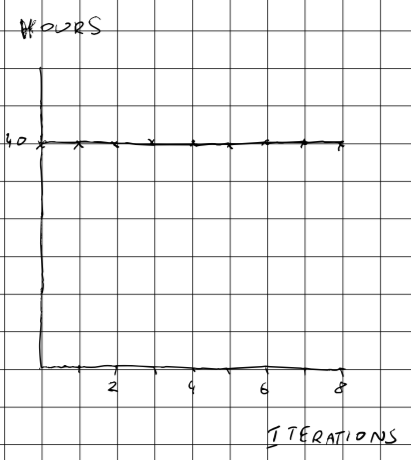

Without knowing anything about your team, I feel confident in stating that the next graph is probably a conservative estimate of how many hours every single person on your team worked per iteration (assuming a one-week iteration):

#+caption:Hours per iteration

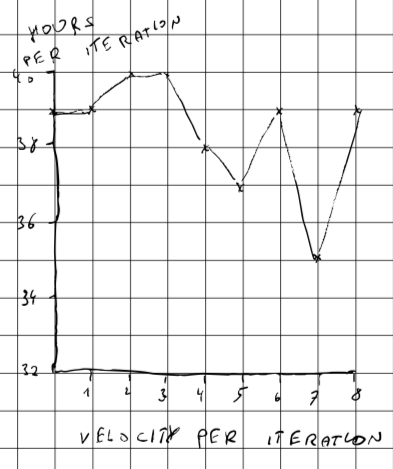

What is more interesting to look at is how many hours it took to deliver the estimated work:

#+caption:Hours mapped to velocity

I'm mapping it to a table below as well:

| iteration | velocity | hours |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 39 |

| 1 | 5 | 39 |

| 2 | 2 | 40 |

| 3 | 10 | 40 |

| 4 | 7 | 38 |

| 5 | 5 | 37 |

| 6 | 7 | 39 |

| 7 | 8 | 35 |

| 8 | 9 | 39 |

What we see here is that the team always delivered on its commitment without working overtime. Go, team! We also see that sometimes, the commitments were reached before all the time was spent. This left the team with time that wasn't committed to story work. This is PERFECT time to do tech debt! Guess what we call this time? We call it slack time.

Let's round this out a bit

A fully utilized highway is a parking lot.

A fully utilized highway is a parking lot. It's the space between the cars which allows the cars to safely move forward, change lanes, join and leave the highway, etc.

We don't want to try maximize time spent, because time spent does not directly correlate to value delivered.

We don't want to estimate tech debt and add it to the velocity because the velocity is only for story work – by creating this restriction, we maintain a correlation between velocity (story work done) and value delivered, to get a sense of how valuable overall the decisions that have led to the work have been.

We want to foster a culture and a practice of continuous improvements and continuous small refactors.

We want to take as little time away from story work (the time used, iteration in and interation out, by the velocity) as possible. Time taken away from story work must be followed by a retrospective in which the team finds a way (or ways) to keep this from happening again.

If time must be taken away from story work, the decision must be the result of a conversation with the product owner/product manager, in which the positive result of the corrective action must be crystal clear (e.g. more trustworthy tests, a specific operation will be easier to code/implement/change, etc.)

Footnotes

Author of "Art of Agile Development"

This, of course, is related to the physics term, where "velocity" is defined to be a change of position in a given direction over time. We could just say that it's "speed", but speed is just distance over time, irrespective of direction, and we very much care that we're going in a direction where we deliver more value.